My Personal Guide to HTTP Requests in Python¶

Author: Mohammad Sayem Chowdhury

Focus: Mastering web communication and API interactions

Essential skills for modern data science and web development

My Journey with HTTP and Python Requests¶

In today's connected world, understanding HTTP requests is crucial for any data scientist or developer. This notebook captures my exploration of web communication using Python's powerful Requests library.

What I'll Master:

- Understand HTTP protocol fundamentals

- Handle various types of HTTP requests

- Process different response formats (HTML, JSON, images)

- Build real-world API interaction skills

Estimated learning time: 15-20 minutes of hands-on practice

Table of Contents

My HTTP Learning Journey¶

What I'll Explore:¶

- HTTP Fundamentals - Understanding web communication

- URLs and their components

- Request structure and methods

- Response formats and status codes

- Python Requests Mastery - Practical implementation

- GET requests with parameters

- POST requests for data submission

- Handling different content types

My Understanding of HTTP - The Web's Communication Protocol¶

HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol) is the foundation of web communication that I use daily. Here's how I understand the process:

When I (the client) request a web page, my browser sends an HTTP request to the server hosting that page. The server locates the requested resource (usually "index.html" by default) and sends back an HTTP response containing the content plus metadata like file type and size.

My mental model: Think of it like ordering from a restaurant - I send a request (order), the server processes it, and sends back a response (my meal) with details about what I'm receiving.

The figure below represents the process. The circle on the left represents the client, the circle on the right represents the Web server. The table under the Web server represents a list of resources stored in the web server. In this case an HTML file, png image, and txt file .

The HTTP protocol allows you to send and receive information through the web including webpages, images, and other web resources. In this lab, we will provide an overview of the Requests library for interacting with the HTTP protocol.

My HTTP Communication Workflow:

[Client (Me)] →→→ HTTP Request →→→ [Web Server]

│

│ Server processes:

│ - HTML files

│ - Images (PNG, JPG)

│ - Data files (JSON, TXT)

│

[Client (Me)] ←←← HTTP Response ←←← [Web Server]

Why this matters for my work: Understanding HTTP is essential for web scraping, API consumption, and building data pipelines that interact with web services.

URL Structure - My Navigation System¶

URLs (Uniform Resource Locators) are my roadmap to web resources. I break them down into three essential components:

My URL Anatomy:

- Scheme: The protocol (usually

http://orhttps://) - Base URL/Domain: The server location (e.g.,

www.github.com,api.openweathermap.org) - Route/Path: The specific resource location (e.g.,

/users/mohammad,/weather/current)

Example from my projects:

https://api.github.com/users/mohammad/repos

- Scheme:

https:// - Base URL:

api.github.com - Route:

/users/mohammad/repos

Professional terminology I use:

- URI (Uniform Resource Identifier): URLs are actually a subset of URIs

- Endpoint: A specific URL that provides a particular service or data - crucial concept for API work

In my data science projects: I often work with REST API endpoints to fetch real-time data, submit analysis results, or integrate with cloud services.

HTTP Requests - My Data Fetching Toolkit¶

Every HTTP interaction consists of a request and response. When I make a GET request, here's what happens:

My Request Components:

- Method:

GET(retrieving data) - Resource Path:

/index.html(what I want) - HTTP Version: Usually HTTP/1.1 or HTTP/2

- Headers: Additional information about my request

Key insight: Headers carry metadata that servers use to process my requests correctly.

HTTP Methods I Use Most in My Projects:

When an HTTP request is made, an HTTP method is sent, this tells the server what action to perform. A list of several HTTP methods is shown below. We will go over more examples later.

My HTTP Methods Toolkit:

| Method | Purpose | My Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| GET | Retrieve data | Fetching API data, downloading files, web scraping |

| POST | Submit data | Sending analysis results, user authentication, form submissions |

| PUT | Update/replace | Updating dataset records, modifying configurations |

| DELETE | Remove data | Cleaning up temporary files, removing outdated records |

| PATCH | Partial update | Modifying specific fields without replacing entire records |

My most common pattern: 90% of my requests are GET (fetching data) and POST (submitting results).

HTTP Responses - Understanding Server Feedback¶

When the server responds to my request, I receive structured information that helps me understand what happened:

My Response Analysis:

- Status Line: HTTP version, status code (200 = success), descriptive phrase (OK)

- Response Headers: Metadata about the content (type, length, encoding)

- Response Body: The actual content I requested (HTML, JSON, image data, etc.)

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Content-Type: application/json Content-Length: 1234 Server: nginx/1.18.0 Date: Thu, 12 Jun 2025 10:30:00 GMT{ "status": "success", "data": [...] }

Professional tip: I always check the status code first to determine if my request succeeded before processing the response body.

Status Codes I Encounter Regularly:

Some status code examples are shown in the table below, the prefix indicates the class. These are shown in yellow, with actual status codes shown in white. Check out the following link for more descriptions.

My Status Code Quick Reference:

| Code Range | Meaning | Common Examples in My Work |

|---|---|---|

| 2xx | Success | 200 OK, 201 Created, 204 No Content |

| 3xx | Redirection | 301 Moved Permanently, 302 Found |

| 4xx | Client Error | 400 Bad Request, 401 Unauthorized, 404 Not Found |

| 5xx | Server Error | 500 Internal Server Error, 503 Service Unavailable |

My debugging strategy: Status codes are my first clue when API requests fail. I've learned to handle each category appropriately in my error handling code.

Python Requests - My Web Communication Toolkit¶

The Requests library is my go-to tool for HTTP communication in Python. It simplifies web interactions and makes API consumption elegant and intuitive. This library has been essential in my data science projects for fetching real-time data, interacting with cloud services, and building automated workflows.

# My essential HTTP toolkit

import requests

print("Requests library imported - ready for web communication!")

print(f"Requests version: {requests.__version__}")

Additional libraries for my HTTP toolkit:

# Supporting libraries for my web data projects

import os # File path management

from PIL import Image # Image processing

from IPython.display import IFrame # Displaying web content

print("Complete HTTP toolkit ready!")

print("Ready to handle: text, images, JSON, and embedded content")

My First GET Request - Fetching Web Content¶

Let me demonstrate a basic GET request to a real website. I'll use IBM's homepage as an example:

You can make a GET request via the method get to www.ibm.com:

# My first HTTP GET request

website_url = 'https://www.ibm.com/'

response = requests.get(website_url)

print(f"Request sent to: {website_url}")

print(f"Response received successfully!")

The response object contains all the information about my request. The most important first check is the status code:

# Checking if my request was successful

status = r.status_code

print(f"Status code: {status}")

if status == 200:

print("✅ Success! The server responded properly")

else:

print(f"❌ Error: Status code {status}")

status

200

Analyzing my request headers - what I sent to the server:

print("=== My Request Headers ===")

for header, value in response.request.headers.items():

print(f"{header}: {value}")

print("\n💡 These headers identify my client and capabilities to the server")

{'User-Agent': 'python-requests/2.24.0', 'Accept-Encoding': 'gzip, deflate', 'Accept': '*/*', 'Connection': 'keep-alive', 'Cookie': '_abck=D0C429A0C2FF9867863E5556B01DBC3C~-1~YAAQbdcLF2z7WmN/AQAAJVDIdAeJIgXFwIOv/9q4dyMBQNZnx4PwftD9Ng1Xu12yI95nIv+NsnxVtbugiIGI48lYE5sWonROECxg4OixEZZRf9Ogxm9C613IIFX8G1v3JxWSlfYXZ96NwuZj3cXM9oHl8AJMEBwmloYbrExR9c71Q9J4EA+vCHIz9iUUwnCuSiBL/vvJWWQa2gM/+GXxcV/lqAyGA1HAda0zUDXp7YDF9AZebHFkKPMNDo1ozP1i0+BktMwbyCJ3l6Vj+wuV5zrI6aKYl8ormfKNdcS14R1HvlLlOXyvZMYtDIKHl7t6+bGAGDoq2lbo9Lj62x/cXcfKG/EsXxli+yocRbV6kWuyN1RSoKc=~-1~-1~-1; bm_sz=3273A448AB007D34BC104F64776E93DA~YAAQbdcLF237WmN/AQAAJVDIdA8OW9c9EwCIW6OeXUVCShN+CiSgkAtnCrvjoef6+Of6Qmfxmx5gutTplMhigbwKpV3aPIMfAje9IZTI0tisIUgwJaNKKq//IQfQZeKQ102z9VxuLACs6QXeSUgPGGHHxAJByIpVoh8v7vowaXdryyjiJOUFOghPCVULod7Giwq+buS7vbcXOxB2xnSmg/k5aGMOKsg0ps2H4WeAMqGq2/+LB48RtNLQSMoUz7vijJaShAz5z23uivk3nhfNsfGAjzSFMYD3FY5GOXAeNt4=~3486534~3753270'}

Checking the request body - GET requests typically don't have body content:

request_body = response.request.body

print(f"Request body: {request_body}")

print("\n💡 GET requests send parameters in the URL, not the body")

request body: None

Analyzing response headers - valuable metadata from the server:

response_headers = r.headers

print("=== Server Response Headers ===")

for header, value in list(response_headers.items())[:8]: # Show first 8 headers

print(f"{header}: {value}")

print(f"\n📊 Total headers received: {len(response_headers)}")

{'Server': 'Apache', 'Server-Timing': 'intid;desc=3256ed69b6a30503', 'x-drupal-dynamic-cache': 'UNCACHEABLE', 'Link': '<https://www.ibm.com/bd-en>; rel="canonical", <https://www.ibm.com/bd-en>; rel="revision", <//1.cms.s81c.com>; rel=preconnect; crossorigin, <//1.cms.s81c.com>; rel=dns-prefetch', 'x-ua-compatible': 'IE=edge', 'Content-Language': 'en-bd', 'Permissions-Policy': 'interest-cohort=()', 'x-generator': 'Drupal 9 (https://www.drupal.org)', 'x-dns-prefetch-control': 'on', 'x-drupal-cache': 'MISS', 'Last-Modified': 'Thu, 10 Mar 2022 06:26:12 GMT', 'ETag': '"1646893572"', 'Content-Type': 'text/html; charset=UTF-8', 'x-acquia-host': 'www.ibm.com', 'x-acquia-path': '/bd-en', 'x-acquia-site': '', 'x-acquia-purge-tags': '', 'x-varnish': '224100786 204775069', 'x-cache-hits': '3', 'x-age': '6043', 'Accept-Ranges': 'bytes', 'Content-Encoding': 'gzip', 'Cache-Control': 'public, max-age=300', 'Expires': 'Thu, 10 Mar 2022 17:07:40 GMT', 'X-Akamai-Transformed': '9 9449 0 pmb=mTOE,1', 'Date': 'Thu, 10 Mar 2022 17:02:40 GMT', 'Content-Length': '9518', 'Connection': 'keep-alive', 'Vary': 'Accept-Encoding', 'x-content-type-options': 'nosniff', 'X-XSS-Protection': '1; mode=block', 'Content-Security-Policy': 'upgrade-insecure-requests', 'Strict-Transport-Security': 'max-age=31536000', 'x-ibm-trace': 'www-dipatcher: dynamic rule'}

Extracting specific header information - when was this response generated:

# Getting the response timestamp

response_date = response_headers.get('date', 'Not provided')

print(f"Response generated on: {response_date}")

print("\n🕰️ This helps me track when data was last updated")

response_date

'Thu, 10 Mar 2022 17:02:40 GMT'

Content-Type header - tells me what kind of data I received:

# Understanding the content type

content_type = response_headers.get('Content-Type', 'Unknown')

print(f"Content type: {content_type}")

print("\n📋 This tells me how to process the response data")

content_type

'text/html; charset=UTF-8'

Character encoding - important for text processing:

# Checking text encoding

text_encoding = r.encoding

print(f"Text encoding: {text_encoding}")

print("\n🔤 Critical for properly displaying international characters")

text_encoding

'UTF-8'

Processing HTML content - extracting the actual web page data:

# Examining the HTML content (first 200 characters)

html_preview = response.text[:200]

print("=== HTML Content Preview ===")

print(html_preview)

print("\n📝 This is the raw HTML that browsers render into web pages")

print(f"Total content length: {len(response.text):,} characters")

'<!DOCTYPE html>\n<html lang="en-bd" dir="ltr">\n <head>\n <meta charset="utf-8" />\n<script>digitalD'

Handling Different Content Types - Working with Images¶

Not all web content is text! Let me demonstrate downloading and processing an image file:

# Working with binary content - downloading an image

image_url = 'https://cf-courses-data.s3.us.cloud-object-storage.appdomain.cloud/IBMDeveloperSkillsNetwork-PY0101EN-SkillsNetwork/IDSNlogo.png'

print(f"Downloading image from: {image_url}")

print("This demonstrates handling non-text content")

Making the image request:

import requests

url = "http://example.com/image.jpg"

# Downloading the image

image_response = requests.get(url)

print(f"Image request status: {image_response.status_code}")

if image_response.status_code == 200:

print("✅ Image downloaded successfully!")

print(f"Content size: {len(image_response.content):,} bytes")

else:

print("❌ Failed to download image")

Analyzing image response headers:

print(r.headers)

# Checking image-specific headers

print("=== Image Response Headers ===")

key_headers = ['Content-Type', 'Content-Length', 'Last-Modified']

for header in key_headers:

value = image_response.headers.get(header, 'Not provided')

print(f"{header}: {value}")

{'Date': 'Thu, 10 Mar 2022 17:02:42 GMT', 'X-Clv-Request-Id': '503ba4f5-fb82-4b47-9ccd-ce7edc38e926', 'Server': 'Cleversafe', 'X-Clv-S3-Version': '2.5', 'Accept-Ranges': 'bytes', 'x-amz-request-id': '503ba4f5-fb82-4b47-9ccd-ce7edc38e926', 'Cache-Control': 'max-age=0,public', 'ETag': '"a831e767d02efd21b904ec485ac0c769"', 'Content-Type': 'image/png', 'Last-Modified': 'Thu, 24 Feb 2022 12:40:34 GMT', 'Content-Length': '21590'}

Verifying the content type - confirming it's actually an image:

# Confirming we received an image

image_content_type = image_response.headers['Content-Type']

print(f"Content type: {image_content_type}")

if 'image' in image_content_type:

print("✅ Confirmed: This is image data")

else:

print("⚠️ Warning: This might not be an image")

image_content_type

'image/png'

Saving binary content - images are bytes-like objects that need special handling:

import os

# Creating the file path for saving

file_path = os.path.join(os.getcwd(), 'downloaded_image.png')

print(f"Saving image to: {file_path}")

file_path

'C:\\Users\\chysa\\IBM\\PY0101EN\\image.png'

Saving the binary content - using the content attribute for binary data:

with open(file_path, 'wb') as image_file:

image_file.write(image_response.content)

print("✅ Image saved successfully!")

print(f"File size: {os.path.getsize(file_path):,} bytes")

print("\n💡 Key insight: Use 'content' for binary data, 'text' for text data")

Viewing the downloaded image - confirming successful download:

from PIL import Image

# Assuming 'path' is defined and points to a valid image file

path = "path_to_your_image_file.jpg"

# Displaying the downloaded image

try:

downloaded_image = Image.open(path)

print(f"Image dimensions: {downloaded_image.size}")

print(f"Image mode: {downloaded_image.mode}")

print("✅ Image loaded successfully for display")

# Note: Image will display in notebook when running

downloaded_image.show()

except Exception as e:

print(f"❌ Error loading image: {e}")

Challenge: Let me recreate the wget functionality using Python requests. I'll download a text file and save it locally - a common task in my data processing workflows.

In the previous section, we used the wget function to retrieve content from the web server as shown below. Write the python code to perform the same task. The code should be the same as the one used to download the image, but the file name should be 'Example1.txt'.

Traditional approach:

wget -O Example1.txt https://cf-courses-data.s3.us.cloud-object-storage.appdomain.cloud/IBMDeveloperSkillsNetwork-PY0101EN-SkillsNetwork/labs/Module%205/data/Example1.txt

My Python approach:

!wget -O /resources/data/Example1.txt <https://cf-courses-data.s3.us.cloud-object-storage.appdomain.cloud/IBMDeveloperSkillsNetwork-PY0101EN-SkillsNetwork/labs/Module%205/data/Example1.txt>

import os

import requests

# My Python implementation of wget functionality

text_file_url = 'https://cf-courses-data.s3.us.cloud-object-storage.appdomain.cloud/IBMDeveloperSkillsNetwork-PY0101EN-SkillsNetwork/labs/Module%205/data/Example1.txt'

local_filename = os.path.join(os.getcwd(), 'my_downloaded_example.txt')

print("=== My Python File Downloader ===")

print(f"Source: {text_file_url}")

print(f"Destination: {local_filename}")

# Downloading the file

text_response = requests.get(text_file_url)

if text_response.status_code == 200:

with open(local_filename, 'wb') as text_file:

text_file.write(text_response.content)

print("✅ File downloaded successfully!")

print(f"File size: {os.path.getsize(local_filename)} bytes")

# Preview the content

with open(local_filename, 'r') as f:

preview = f.read(100)

print(f"\nContent preview: {repr(preview)}...")

else:

print(f"❌ Download failed with status code: {text_response.status_code}")

Click here for the solution

url='https://cf-courses-data.s3.us.cloud-object-storage.appdomain.cloud/IBMDeveloperSkillsNetwork-PY0101EN-SkillsNetwork/labs/Module%205/data/Example1.txt'

path=os.path.join(os.getcwd(),'example1.txt')

r=requests.get(url)

with open(path,'wb') as f:

f.write(r.content)

My approach advantages:

- More control over the download process

- Better error handling capabilities

- Integration with larger Python workflows

- Cross-platform compatibility

Get Request with URL Parameters

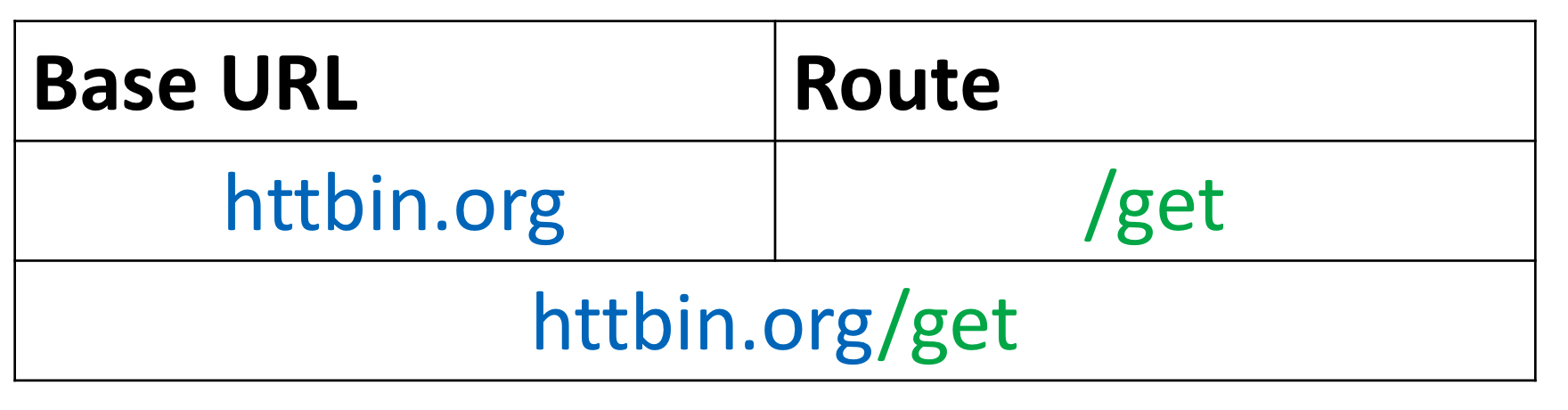

You can use the GET method to modify the results of your query, for example retrieving data from an API. We send a GET request to the server. Like before we have the Base URL, in the Route we append /get, this indicates we would like to preform a GET request. This is demonstrated in the following table:

The Base URL is for http://httpbin.org/ is a simple HTTP Request & Response Service. The URL in Python is given by:

url_get='http://httpbin.org/get'

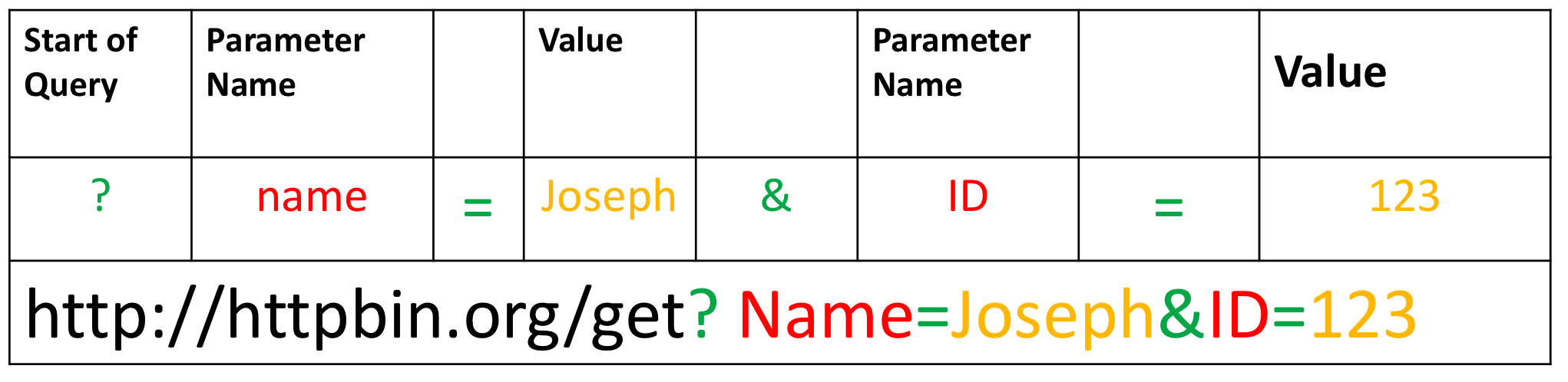

A query string is a part of a uniform resource locator (URL), this sends other information to the web server. The start of the query is a ?, followed by a series of parameter and value pairs, as shown in the table below. The first parameter name is name and the value is Joseph. The second parameter name is ID and the Value is 123. Each pair, parameter, and value is separated by an equals sign, =.

The series of pairs is separated by the ampersand &.

To create a Query string, add a dictionary. The keys are the parameter names and the values are the value of the Query string.

payload={"name":"Joseph","ID":"123"}

Then passing the dictionary payload to the params parameter of the get() function:

r=requests.get(url_get,params=payload)

We can print out the URL and see the name and values

r.url

'http://httpbin.org/get?name=Joseph&ID=123'

There is no request body

print("request body:", r.request.body)

request body: None

We can print out the status code

print(r.status_code)

200

We can view the response as text:

print(r.text)

{

"args": {

"ID": "123",

"name": "Joseph"

},

"headers": {

"Accept": "*/*",

"Accept-Encoding": "gzip, deflate",

"Host": "httpbin.org",

"User-Agent": "python-requests/2.24.0",

"X-Amzn-Trace-Id": "Root=1-622a2f33-188e42b4621ab3165e41d47a"

},

"origin": "160.202.146.112",

"url": "http://httpbin.org/get?name=Joseph&ID=123"

}

We can look at the 'Content-Type'.

r.headers['Content-Type']

'application/json'

As the content 'Content-Type' is in the JSON format we can use the method json(), it returns a Python dict:

r.json()

{'args': {'ID': '123', 'name': 'Joseph'},

'headers': {'Accept': '*/*',

'Accept-Encoding': 'gzip, deflate',

'Host': 'httpbin.org',

'User-Agent': 'python-requests/2.24.0',

'X-Amzn-Trace-Id': 'Root=1-622a2f33-188e42b4621ab3165e41d47a'},

'origin': '160.202.146.112',

'url': 'http://httpbin.org/get?name=Joseph&ID=123'}

The key args has the name and values:

r.json()['args']

{'ID': '123', 'name': 'Joseph'}

Post Requests

Like a GET request, a POST is used to send data to a server, but the POST request sends the data in a request body. In order to send the Post Request in Python, in the URL we change the route to POST:

url_post='http://httpbin.org/post'

This endpoint will expect data as a file or as a form. A form is convenient way to configure an HTTP request to send data to a server.

To make a POST request we use the post() function, the variable payload is passed to the parameter data :

r_post=requests.post(url_post,data=payload)

Comparing the URL from the response object of the GET and POST request we see the POST request has no name or value pairs.

print("POST request URL:",r_post.url )

print("GET request URL:",r.url)

POST request URL: http://httpbin.org/post GET request URL: http://httpbin.org/get?name=Joseph&ID=123

We can compare the POST and GET request body, we see only the POST request has a body:

print("POST request body:",r_post.request.body)

print("GET request body:",r.request.body)

POST request body: name=Joseph&ID=123 GET request body: None

We can view the form as well:

r_post.json()['form']

{'ID': '123', 'name': 'Joseph'}

There is a lot more you can do. Check out Requests for more.